- Details

- Written by: Carlos Delgado

In engineering and industrial construction projects—particularly in sectors like mining, energy, or infrastructure—contractual conflicts are not an anomaly, but a foreseeable reality. Claims for schedule extensions, cost overruns, scope changes, or underperformance arise frequently, putting the technical, contractual, and leadership capabilities of project teams to the test.

In these situations, negotiation is not optional—it's a critical skill. Done well, it makes the difference between a viable technical solution and a costly dispute that paralyzes the project. That’s why effective negotiation should be understood as a strategic project management function, requiring preparation, structure, and professional rigor.

Beyond Bargaining: Negotiating with Purpose

Negotiation is not about “winning.” In complex environments, where all parties risk losses if the project stalls, the only sustainable agreements are those that meet the core interests of all stakeholders. This principle forms the foundation of the collaborative negotiation model developed at Harvard’s Negotiation Program (Fisher & Ury, Getting to Yes), and it remains a key tool for modern project leaders.

The essential principles of this approach are:

- Separate people from the problem: Distinguish technical issues from emotional reactions.

- Focus on interests, not positions: Identify what each party truly needs—not just what they demand.

- Invent options for mutual gain: Design creative solutions that generate shared value.

- Use objective criteria: Anchor discussions in data, standards, and validated references.

These principles go beyond contractual disputes—they’re useful in resolving technical issues, coordinating between contractors, and re-aligning delayed or disrupted projects.

From Conflict to Resolution: The Power of Perspective

In a recent article, I shared a personal experience from 2009—a routine technical visit to a hydroelectric plant that unexpectedly turned into a hostage situation due to a local community protest (https://delgadoconsultores.pe/index.php/en/articles/negotiating-in-hostile-terrain-a-true-lesson-in-leadership-and-empathy). Despite having no negotiation training at the time, the way forward emerged from applying core principles: understanding the other party, breaking down the problem, and finding common ground through empathy.

While the context of a construction project is different, the logic remains: posturing escalates conflict; insight and structure de-escalate it.

Common Negotiation Scenarios in Projects

Typical project scenarios where effective negotiation is essential include:

- Claims for unforeseen site conditions: A contractor demands compensation and schedule relief due to unexpected geotechnical challenges. Resolving the issue requires technical analysis and fair allocation of risk.

- Redesign during construction: Updated drawings disrupt the work plan. The contractor requests a price adjustment, the owner insists on original rates. Resolution requires disaggregating impacts and using market benchmarks.

- Delays and acceleration demands: A project falls behind. Recovery is needed, but budgets are tight. The challenge is to negotiate re-sequencing, prioritization, and shared performance incentives.

In each case, interest-based negotiation supported by technical evidence delivers workable, lasting agreements. In contrast, pressure-driven or positional negotiation often leaves open wounds and hidden costs.

Practical Strategies for Professional Negotiation

To negotiate effectively in a complex setting, preparation and structure are key. Some practical strategies include:

- Technical and contractual preparation: Know the details—contracts, schedules, designs, and on-site data. No information, no negotiation.

- Break down the dispute: Segment the issue into manageable parts. Not everything is in conflict—focusing efforts reduces friction.

- Uncover real interests: Understand what the other side really needs—cash flow, schedule relief, risk protection, or reputational safety.

- Use precedents and standards: Leverage technical norms (e.g., AACEI, FIDIC), forensic schedule analysis, and cost benchmarking.

- Offer multiple options: Don’t present just one solution—provide two or three viable, data-supported alternatives.

- Document the agreement: Translate the negotiation into formal, auditable documents: letters, change orders, or contractual amendments.

The Role of a Specialized Consultancy

When tensions rise or progress stalls, a neutral and experienced technical third party can unlock negotiations. A consultancy with expertise in contract management, forensic analysis, and project leadership brings perspective, structure, and credibility.

At DC&R, we support our clients by:

- Leading or advising in complex project negotiations.

- Identifying viable scenarios and preparing supporting documentation.

- Conducting independent technical analyses (schedules, costs, productivity) to substantiate proposals.

- Mediating between contractors, owners, and stakeholders in high-pressure environments.

Our approach is technical, pragmatic, and results-driven: building agreements that work while protecting the business case.

Final Thoughts: Negotiating Well is Leading Wisely

In complex projects, negotiation isn’t about yielding or winning—it’s about leading the conflict toward resolution. And that demands more than instinct or seniority. It requires method, technical rigor, and strategic clarity.

If your organization is facing contractual disputes, stalled negotiations, or critical decisions with cost and schedule impacts, we can help.

📩 Contact DC&R to explore how we can support your project with an effective, technically grounded negotiation strategy.

- Details

- Written by: Carlos Delgado

This is a different kind of article—less technical, more personal—like the time I wrote about the installation of the chimneys at Larcomar. It’s a personal story with lessons applicable to negotiation in business environments.

I hesitated a bit on how to title it, because it’s about negotiation, but I wasn’t directly negotiating anything work-related. Well, technically, it was a work matter—just in a rather indirect way.

It was 2009, and the company I worked for, FIANSA, was going through a period of low sales. Our business was engineering and manufacturing of steel structures, as well as the construction and electromechanical erection of heavy industrial projects—including commissioning of hydroelectric plants.

As part of the sales effort, the general manager, the head of engineering, and I (operations manager) headed out to a scheduled meeting to assess the feasibility of taking on the El Platanal Hydroelectric Plant project, which at the time had progressed approximately 70% in infrastructure. The project owner had signed a contract with Odebrecht, one of our regular clients back then, for parts of the work.

The project faced social conflict due to concerns from farmers in Lunahuaná and Cañete about potential impact on the river flow.

We left Lima early on a weekday. The approximately 180 km route was expected to take around 3.5 hours, though our plan included a breakfast stop at the well-known “El Piloto” restaurant in Cañete.

After a great breakfast and in good spirits, we continued the trip, expecting no more than 1.5 hours to go. Unfortunately, a surprise awaited us in the final stretch of the road.

About half an hour after resuming our journey, as we passed the entrance to a small town, some locals signaled for us to turn off and enter the village. Thinking they were warning us of a problem on the road, we entered.

As soon as we got in, we saw several other vehicles stopped and many locals surrounding them. Most of the villagers were carrying long sticks (those of us who were Boy Scouts would call them “staffs”). We couldn’t move forward, and several of the villagers—armed with those staffs—had surrounded us and blocked our rented car (with driver) from reversing.

We had been taken hostage, in a place without even mobile signal coverage!

It was a situation I had never experienced, and I was scared. My first instinct was to tell the driver to reverse no matter who he ran over, to get us out. Something in my brain told me that wasn’t a good idea. We could seriously hurt someone, and the villagers’ reaction would be extreme and violent. They were too many. So my first real action was to stay quiet and study the situation with as much calm as I could manage.

We quickly coordinated among ourselves and rolled down the windows to ask what was happening—why we were being stopped. The reason was the villagers’ opposition to the project. They were stopping everyone headed to the El Platanalplant.

We explained that we didn’t even work there. This was our first visit to see if we’d be invited to bid. Clearly, the villagers didn’t care. They had decided to oppose the project and would detain everyone passing through until they were heard or the project was stopped.

Then I noticed something. The men—all armed with staffs—were clearly aggressive, but they weren’t in charge. They were just soldiers, the security force. The ones in charge were the women. They weren’t armed, but they were the ones making decisions and giving orders.

The leader closest to us—a middle-aged woman—told us we wouldn’t be harmed, but we wouldn’t be allowed to leave. I started to think about what we could do. We consulted with each other and took turns repeating that we had no involvement with the project.

After a while, I asked the woman by our car for permission to go to the bathroom. She agreed. On my way back, I stood by the car and started talking to her. I told her I was married and had a three-year-old daughter. I pointed to my colleagues. My boss, the general manager, was also married, and his first daughter was slightly younger than mine. The head of engineering also had a family and had traveled from Trujillo, some 550 km north of Lima, to join us on this visit.

I expressed our fears, and she tried to reassure us—they had no intention of harming anyone. I explained that she might know that, but from our point of view, we only knew that we were being detained—taken hostage by armed people—for no fault of our own, and we feared for our safety and for our families.

Then I asked if she had children. Yes, she said—at least one of them was an adult and working. Well, I said, there are four of us in this car. Three of us are company officials and made the decision to come. But the driver was hired by the rental company—he was just doing his job, earning a living. He didn’t choose to come here. He was ordered to drive us.

I said: Imagine your son gets a good job as a driver at a formal company that pays decently and offers benefits. One day, simply doing his job, he ends up being held by force in a community like this—far from home, unable to contact his family or employer. Wouldn’t your son be scared? Wouldn’t you be scared if you found out about his situation?

That’s when this woman internalized the situation from our point of view. We weren’t defending the project. We didn’t even argue whether it was good or bad. We were human beings like her—with families—caught in a terrible situation. One of us could’ve been her son.

“Alright,” she said. “You can go.” She told the armed men to let us pass. They cleared the way.

“Thank you very much,” I said, immediately jumped into my seat, and told the driver, “Go, now!”

“What did you tell her?” my colleagues asked. I don’t remember exactly what I replied—something about telling the truth and making her see the driver’s situation. After all, she was a mother.

Shortly afterward, I took a negotiation workshop on the “Harvard method.” It’s about negotiating based on interests, not positions. A win–win. At the time of the incident, I didn’t know that. But without realizing it, what I did that day was find common ground. We became two parties who agreed that the problem wasn’t each other—it was external to us, and we had no reason to fight. In fact, we had more similarities than differences.

Those are the same principles we apply today in DC&R’s services—contract negotiation, conflict resolution, analysis of interests vs. positions—and they remain the best path toward solutions that work for all parties involved.

In times of change, where agility and efficiency are essential at every level, relying on specialized services provides the right blend of capability, effectiveness, and efficiency that organizations need to succeed.

At DC&R, we meet those needs with professional reliability and over 30 years of experience in complex engineering and construction environments for demanding industrial sectors such as mining, oil & gas, energy, and infrastructure.

We also offer technical assistance to businesses that need to engage with engineering and construction firms—from managing tenders and projects to contractual administration.

📧

🌐 https://delgadoconsultores.pe/index.php/es/

- Details

- Written by: Carlos Delgado

Introduction

In the management of complex industrial projects, such as those in the mining, energy, and infrastructure sectors, time control is a critical factor that can determine the success or failure of an initiative. Delays not only generate cost overruns and penalties but can also affect the expected return on investment and deteriorate contractual relationships between the parties involved.

In this context, forensic schedule analysis emerges as a strategic tool that should not be seen solely as a reactive resource for dispute resolution, but as a practice of prevention, control, and technical support that strengthens decision-making throughout the entire project life cycle.

What is Forensic Schedule Analysis?

Forensic schedule analysis is a specialized methodology that identifies, evaluates, and quantifies delays that have occurred during project execution. Its purpose is to determine the root causes of deviations, establish responsibilities, and measure the actual impact of specific events on the critical path and contractual completion date.

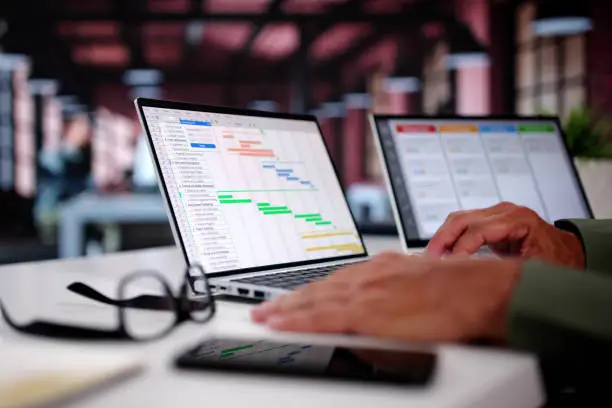

Unlike simple progress monitoring, forensic analysis employs internationally recognized, structured techniques such as Time Impact Analysis (TIA) and Windows Analysis, which allow for the historical reconstruction of the schedule with documentary support and technical traceability.

Strategic Benefits of Forensic Analysis

The value of forensic schedule analysis extends far beyond dispute resolution. When properly applied, it offers strategic benefits that directly impact project management:

1. Claim Prevention and Contractual Strengthening

A schedule rigorously analyzed enables early identification of risk scenarios, the preparation of solid contractual defenses, and the prevention of claims from escalating into formal disputes. Forensic analysis provides objective foundations that strengthen the client's technical position against contractors and third parties.

2. Decision-Making Support

Having detailed information on the causes of delays facilitates informed decision-making, both to mitigate ongoing impacts and to adjust execution strategies. For example, it allows for the evaluation of whether it is advisable to accelerate specific activities, reprogram resources, or renegotiate contractual conditions.

3. Business Case Protection

Forensic analysis helps measure the real impact of delays on cash flow, indirect costs, and commercial project milestones, which contributes to protecting the economic value of the project and minimizing losses due to inadequate decisions or the misallocation of responsibilities.

4. Technical Support in Dispute Resolution Processes

When controversies evolve into formal conciliation, arbitration, or litigation processes, forensic analysis reports become essential technical elements to substantiate positions and defend interests with objectivity and traceability.

Practical Applications in Industrial Projects

Based on the experience of DC&R – Delgado Consultoría & Representaciones, we have found that forensic schedule analysis adds value in various scenarios:

- Mining projects executed under the EPCM model, where partial supervision of contractors generates grey areas in the responsibility for delays. Forensic analysis clarifies responsibilities and ensures that unjustified costs are not passed on to the client.

- Energy infrastructure projects where the simultaneous work of multiple fronts requires a precise reconstruction of the impact of interferences, access restrictions, and engineering changes on the contractual schedule.

- Public and private construction contracts where schedule management is closely linked to payment milestones and penalties, making it essential to have structured chronological evidence to support claims or defend positions in contract reviews.

Conclusions

Forensic schedule analysis is an indispensable tool for the efficient management of industrial projects. Its true value lies not only in resolving conflicts but in preventing deviations, supporting critical decisions, and protecting the project's economic model.

Proactively adopting this practice enables organizations to anticipate adverse scenarios, strengthen their contractual positions, and optimize their execution strategies with a comprehensive view that connects planning with business profitability.

At DC&R – Delgado Consultoría & Representaciones, we have specialists in forensic schedule analysis with extensive experience in complex industrial projects. If your organization faces contractual challenges or needs to reinforce schedule control, we are ready to support you with technically responsible solutions aligned with your business objectives.

In times of change, when agility and economy are needed at all levels, the use of specialized services provides that precise mix of capacity, effectiveness and efficiency that organizations need to succeed.

At DC&R we are able to meet these requirements with professional solvency and the experience of more than 30 years in complex engineering and construction environments for heavy industrial markets of high demand such as mining, gas & oil, or energy, as well as for infrastructure and commerce.

DC&R also offers technical assistance services to businesses that need to interact with engineering and construction companies, from tender and project management to contract administration.

- Details

- Written by: Carlos Delgado

In November 2020, I published an article titled simply “Risk Management.”(https://delgadoconsultores.pe/index.php/en/articles/risk-management) In it, I proposed a notion that I continue to support even more firmly today: risk management is not just a technical procedure or a line item in the project plan. It is, increasingly, a core strategic leadership tool.

Five years later, the need for anticipation, agility, and control is no longer a competitive advantage—it’s a basic condition for executing successfully. This is where a well-applied risk management system becomes crucial. When implemented properly, it not only mitigates negative impacts but enables informed decisions, improves margins, and aligns teams around clear priorities and responses.

What has changed since 2020?

The theoretical framework remains the same: planning, identification, analysis, and response. But its practical application has evolved:

- Risks are now more interdependent. A delayed international supplier doesn’t just affect the schedule—it may trigger contractual clauses, increase indirect costs, and disrupt logistics.

- Volatility has become structural. Extreme weather, rising material costs, political or regulatory instability—what used to be unlikely is now routine. Risk matrices must be updated frequently and grounded in real-time data, not just past experience.

- Risk management is no longer exclusive to large-scale projects. Even mid-sized projects now require defined risk structures to avoid overruns, stoppages, or avoidable disputes.

The gap between risk identification and risk management

In many projects, risks are identified but not managed. A risk gets noted, mentioned in a meeting, entered into a spreadsheet—but no one owns it, no response plan is developed, and no monitoring takes place. And when it materializes, it’s too late.

Effective risk management requires:

- Named and empowered risk owners

- Clear, budgeted response plans

- Active monitoring and regular updates to the risk register

- Full integration with project controls (cost, time, quality, and safety)

What does DC&R do differently?

At DC&R, we embed risk management across the entire project lifecycle. It’s not a side task—it’s built into planning, contract strategy, execution model, and control systems. Specifically:

- We design risk breakdown structures (RBS) aligned with contract type, project interfaces, and client profile.

- We lead cross-functional risk workshops, involving operations, logistics, safety, and project control teams.

- We apply prioritization matrices with clear technical and economic criteria.

- We develop practical response plans, prioritizing mitigation when transfer isn’t efficient or cost-effective.

- And above all, we promote active management: mapping risks isn’t enough—action is required.

Conclusion

Risk management is no longer a methodological exercise; it’s a strategic leadership tool. An organization that manages risk in a structured way makes better decisions, anticipates problems, and executes more efficiently.

At DC&R, we’ve supported clients in mining, oil & gas, energy, and infrastructure for over 30 years—especially in high-uncertainty contexts where each unmanaged risk becomes a loss and every timely decision makes a difference.

📩

📞 +51 998 070 145

— DC&R: Project leadership with foresight, strategy, and proven technical experience

- Details

- Written by: Carlos Delgado

Introduction: From Development to Execution

In our 2021 article, “Project Development” (https://delgadoconsultores.pe/index.php/en/articles/projects-development), we emphasized the need for adequate and complete design to ensure the technical and economic viability of any initiative, whether a single-family home or an industrial plant. Today, we take that foundation further: how that design directly affects the proper execution of the work and, therefore, the success of the project. We begin with that methodological basis (FEL, stage gates, contract scheme selection) and move toward the phase where design materializes on-site, because that is where the initial projections are validated—or disproved.

1. Design as the Pillar of Execution

A good design is not just plans, calculations, and specifications. Its main purpose is to provide a sufficiently detailed roadmap so that, during construction, there are no technical gaps or ambiguities:

1. Consistency between scope, engineering, and planning

- The design must be closely integrated with the schedule and budget (PV, Planned Value). If basic engineering deliverables (FEL-3) omit interface details or site conditions, the PV curve will be based on inaccurate assumptions, causing early deviations.

2. Early identification of risks and constraints

- During FEL-2 and FEL-3, trade-offs between design alternatives should consider constructability variables—access, logistics, availability of specialized labor—that directly affect execution speed (EV, Earned Value) and resource consumption (AC, Actual Cost).

3. Standardization and document consistency

- A clear design package—narratives, drawings, material lists, technical specifications—reduces construction-phase queries, shortens procurement approval cycles, and avoids misunderstandings with subcontractors. The more airtight the information package, the lower the friction in the EPC phase (Engineering, Procurement, Construction).

2. How Design Influences Operational Efficiency

The link between design and execution is manifested in two main dimensions:

2.1 Productivity and Performance

Precise activity definitions: A WBS (Work Breakdown Structure) based on detailed design allows each activity to have clear quantity, resource, and duration parameters. This helps estimate performance more accurately—e.g., cubic meters excavated per day, square meters of lining per shift—and reduces the gap between PV and EV in early milestones.

Less rework: A design that incorporates constructability tolerances, weld details, mechanical joints, or piping intersections avoids having to redo completed work. Every on-site adjustment translates to cost overruns (AC > EV) and delays on the critical path.

2.2 Change Management and Variations

Synergy with project control systems: A well-defined design allows rapid quantification of cost impacts (new unit prices) and schedule adjustments (critical path analysis) when the client requests a change. This speeds up the issuance of change orders and reduces contractual disputes.

Contingency prevention: When the design includes geotechnical studies, load modeling, or archaeological/environmental reports, it reduces field uncertainty. For instance, knowing in advance about unexpected rock strata allows planning for specialized drilling equipment, avoiding unplanned stoppages.

3. Contract Scheme Selection and the Role of Design

How responsibility for design is transferred into execution can optimize (or compromise) the final result:

1. Design-Bid-Build

- Advantage: Clear responsibility split between designer and contractor.

- Risk: Disconnection during construction. If the design lacks “lessons learned” from similar projects, the contractor will face inefficiencies when requesting RFIs, creating bottlenecks.

2. Design-Build

- Advantage: Contractor leads design from a conceptual basis. This fosters coordination and reduces interface conflict.

- Risk: Owner cedes some technical control. If the contractor prioritizes margins over constructability, suboptimal design solutions may appear once risk is passed to subcontractors.

3. EPC / EPCM

- Advantage: Full risk transfer for design and procurement to the EPC contractor. If the design is robust, the contractor can negotiate better conditions with suppliers and subcontractors, achieving scale economies and on-time delivery.

- Risk: Contractor assumes redesign costs. With scope changes or unanticipated conditions, contract rigidity may expose them to claims.

4. IPD and PPP

- Advantage: Strong collaboration from conceptual design. Input from architects, engineers, contractors, and end users optimizes execution flow.

- Risk: Requires high participant maturity and complex contracts to align incentives. If stakeholder interests clash during design, integration benefits are lost.

5. The Value of DC&R Experience

As a complement to what we outlined in 2021, at DC&R we’ve found that the key difference between successful projects and those plagued by rework, disputes, or broken schedules lies in:

1. Engineering Package Quality: Designs with a “buildable” level of detail and early constructability reviews.

2. Early Stakeholder Integration: Involving operations and maintenance avoids surprises during startup.

3. Effective Control and Reporting Systems: Applying Earned Value Management (EVM) to monitor PV, EV, and AC in alignment with design.

4. Appropriate Contract Strategy: Selecting the right model (DBB, DB, EPC, IPD) according to project type, client risk tolerance, and technical uncertainty.

Our senior team, with over 30 years’ experience in mining, oil & gas, energy, and infrastructure, has applied these practices in projects of varying scale, quantifying the tangible benefits in cost savings, shorter timelines, and minimized disputes.

Conclusion

A solid design aligned with the execution strategy is not a cost; it is an investment that greatly increases the likelihood of success in any engineering and construction project. If in 2021 we explored “Project Development” from an approval-stage perspective, today we reaffirm that properly materializing that design in the field is the true challenge that separates profitable projects from those that become sources of loss.

If you want to ensure that your projects are built on integral design and executed without surprises, trust DC&R. Our expert team will support you with:

* Engineering package review and optimization

* Advisory on contract scheme selection (DBB, DB, EPC, IPD, PPP)

* Project control system implementation (EVM, WBS, daily reporting)

* Early stakeholder coordination and constructability validation

📩

📞 +51 998 070 145

https://delgadoconsultores.pe/index.php/es/

— DC&R: Your strategic partner in project and engineering management, turning designs into reliable results